Dissertation Project

Electoral Markets on the Move: Migration and Migrants in Latin America:

My three-paper dissertation revolves around the relationship between migration, public goods provision, and political participation in the Global South, emphasizing Latin America. The study of migration has been primarily focused on international movements towards advanced industrialized nations. However, the most extensive population changes are happening in developing countries where rural to urban migration is increasing. In fact, the World Bank expects that nearly 7 out of 10 people will be living in cities during 2050 (World Bank, 2021)). Moreover, some middle-income and low-income countries have become home for residents of other countries due to conflict, state failure, or natural disasters. All of this paints a picture where the analysis of the effects of migration in resource-constrained environments becomes crucial as questions about the provision of public goods and distributional policies intended to include these new individuals in local markets become prescient. This proposal focuses on how local politicians respond to migrant population shocks in their electoral markets and the long-run effects of those shocks in contemporary political attitudes. Overall, I argue that these migration flows create new mobile electorates that can present opportunities or challenges for local politicians concerning the distribution of public goods and services. More particularly, I explain how migration movements transform distributional policies, the politicians’ choice of xenophobic discourses, and the long-run changes in support for affirmative action policies.

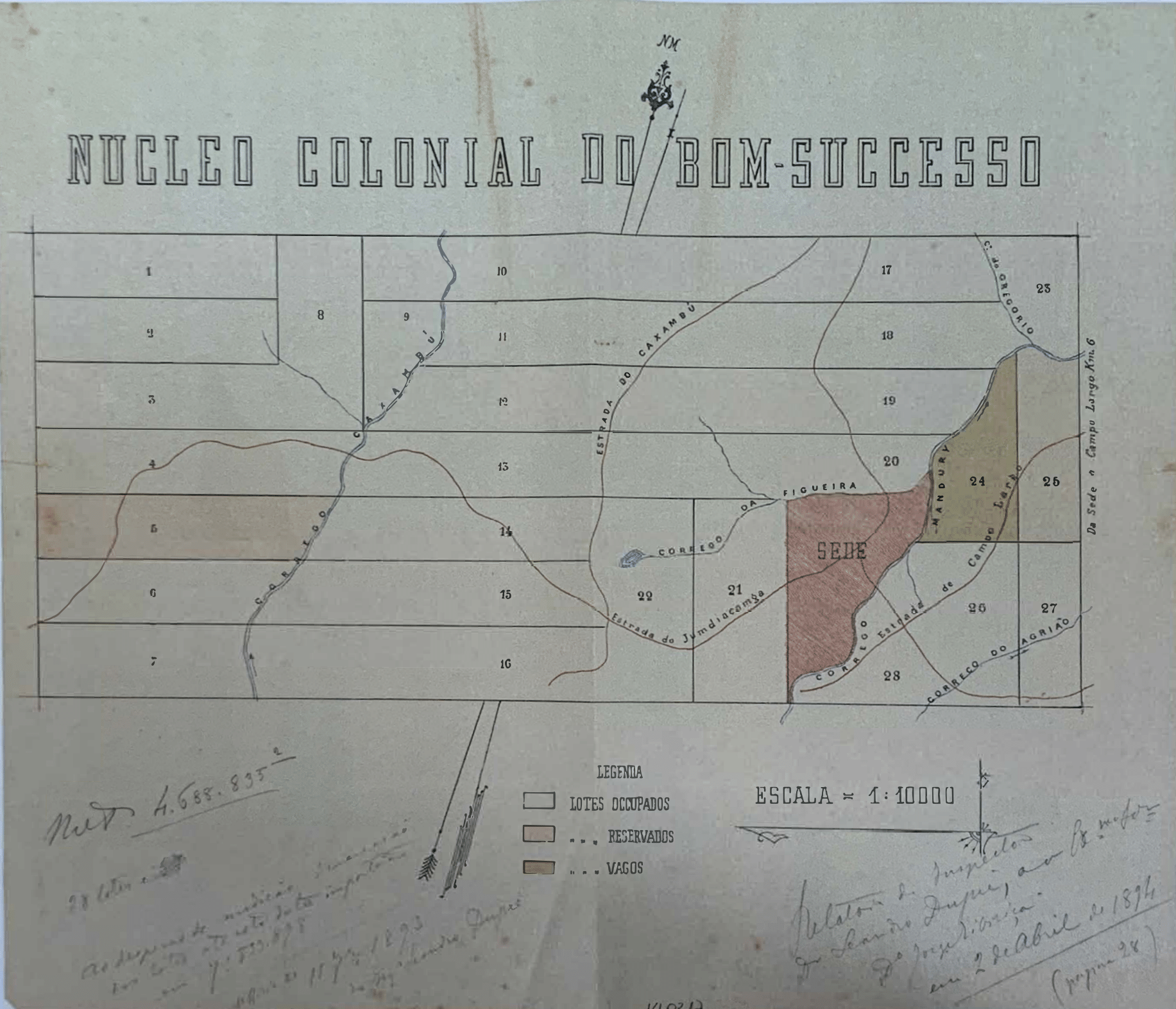

Historically, countries have used migration as a tool to populate empty regions or to supply labor to nascent economies. But what are the long-term effects of these policies? Empirically, I focus on the case of Brazil during the age of Mass Migration (1880-1930) to understand how diverse local migration policies explain the contemporary geography of support for redistribution and affirmative action. During that earlier age, Brazil offered land and labor to attract European migrants to work on the growing coffee sector in the country’s South. Combining an original survey with archival and administrative data, I contend that places that gave land to migrants are less supportive of affirmative action policies, are more anti-distribution, and are more anti-migration today. I argue that this effect is a result of the preservation and strengthening of racial and social hierarchies in Brazilian society that have been transmitted through generations. This paper is the foundation for my first book project on the long-term consequences of migration policies in the developing world.

These historical trends help explain the origins of preferences for redistribution and migration. The other two papers of my dissertation explore the responses of political elites in the developing world to more contemporary migratory movements that add fiscal pressures on local governments. One explores the political economic trade-offs and the other the determination of campaign strategies. Under this framework, local politicians could rhetorically isolate/integrate migrants or incorporate them in their public policy coalitions.

First, I ask how local politicians respond to the emergence and influx of new voters as a result of internal migration. I focus on the case of internally displaced people in Colombia to analyze this question. Despite being more vulnerable and theoretically cheaper to buy, I inquire why not all politicians include migrants in their vote-buying networks. I argue that politicians distribute more private benefits to migrants at lower levels of political competition. This result, I contend, is driven by the fact that migrants present a riskier investment for politicians during competitive races but a source of party building during uncompetitive ones. I use Colombian administrative data and a shift-share instrument in this paper to test my argument.

Second, I study when and why politicians target migrants with polarizing hate speech. Focusing on the arrival of millions of Venezuelan migrants in Colombia I scrape hundreds of thousands of local Colombian newspapers and deploy natural language processing to understand the circumstances under which mayoral and gubernatorial candidates use anti-migrant rhetoric for electoral gain. In this paper, I argue that the electoral uncertainty of the politician and the economic distance between the migrants and the natives determines the use of anti-migrant rhetoric. For this paper, I partner with a Colombian civic organization that works on hate speech in Andean countries in addition to the Machine Learning for Peace Project to scrape newspapers and social media for candidates for the 2023 local elections in Colombia.